This part of South Sudan is dry…so very dry and hot. I walk to school every day through the river bed. There is so rarely water in the rivers that the roads run straight through. Even if there was money to build bridges, I can’t imagine they would bother in most cases. There is one bridge in Narus and conveniently it is just a little further up the river from where I cross. So, when it rains I can take the bridge to school instead.

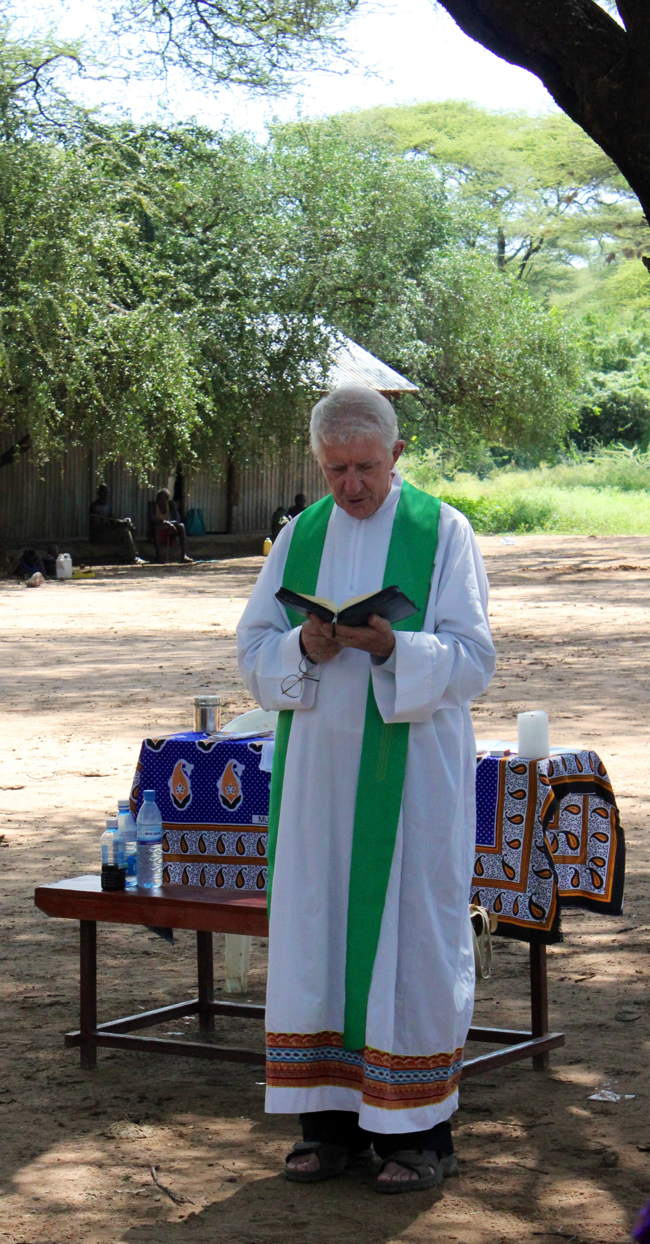

It rained last Saturday morning. Tim and I drove to the church for mass at 7am. Sometime around the second reading the heavens opened. The rain fell against the tin roof completely drowning out every word Fr. Tim said. And the the win added to the drama. Gusts blew great torrents of water through the ventilation space in the roof of the church drenching us all. So we moved to the other side of the church and continued.

Just after Communion, there was an almighty crashing noise. It sounded as though something had crashed against the metal door of the church. Or very loud gunfire maybe. By the time I reacted I saw that my girls from standard 8 were already under the pews looking terrified. We all giggled when we realised that we’d all had such a fright from a clap of thunder. From where Fr. Tim sat he could see the lightening strike almost immediately outside the church.

What struck me deeply though was that this was not the first time the girls had run for cover like that. They grew up in South Sudan during the war. Narus was bombed many times. The girls were accustomed to hearing jets overhead from Khartoum and knew the signal to sprint to their designated bunkers. There are bunkers everywhere. There are at least three in our compound and many more in the girls primary school. I thought how fortunate I was that the reality of my childhood was so very different to theirs.

By the time we were ready to leave, the pickup was full of my students and we took off. We dropped the girls off at the bridge and continued the short distance to our compound. When it rains here, the road turns to mud often several feet deep. And then we got stuck! Tim declared it so matter of factly that there didn’t seem any point encouraging him to try again!

I got out of the pickup to investigate and I established that if we could just move one large stone we should be able to proceed. So…when my girls returned to see what all the commotion was about, they found their maths teacher barefoot in a foot and half of mud trying to loosen a big stone from under the pickup. Needless to say they thought this was the funniest thing they were likely to see all week!!

Anyway, my efforts were futile and we ended up calling Mongi (our mechanic) to come with the tractor and save us. When a task seems just too large, a man on a Massey Ferguson can always fix it!!

It rained on Wednesday too but I’m afraid it wasn’t quite such a giggle. It rained quite heavily for about 3 hours from 5am. I made it to school safely through the mud but on my way back to the compound after my morning classes I met Sr. Agnes who told me that there had been an accident.

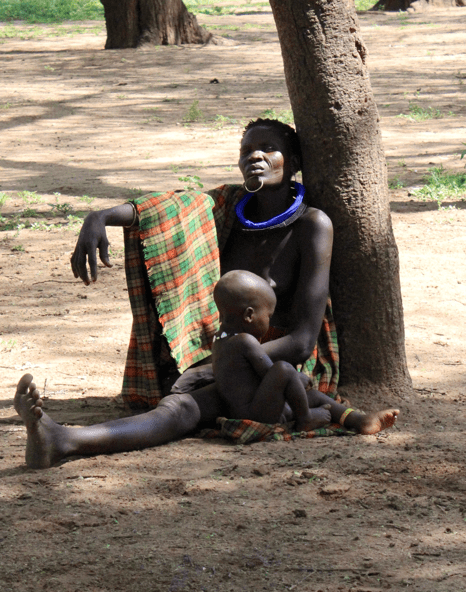

About 20 Toposa women had stayed at our compound for two nights. They had been in Kenya and Uganda to have peace talks with the Turkana and the Karamajong. There is a long history of violence and war between the three tribes. They had a good trip and productive discussions.

Their villages are about 6 hours drive into the bush from Narus. They travelled in the back of a truck. Apparently the truck hit a pothole which was actually mud many feet deep and the truck toppled over. The women were thrown from the back of the truck.

It is a miracle that no one died or suffered more severe injuries. Two doctors were dispatched from ARC (American Refugee Centre) and the driver from our compound left in another truck. Three women were admitted to the government clinic and the others returned to our compound to rest after their ordeal.

Life is back to normal now after the rain….but my Daddy was (as always right)….I should have packed my wellies!